09 May 2025

Unfortunately, my role at my current company is being eliminated, so I am looking for new employment. Here’s a little bit about me and what I do.

I’m Jason Biatek, a software engineer with a master’s in computer science. I have a history in academia/research (see my publications on the About page of this blog), but more recently have been doing more with customer service engagements and product-focused projects. You can reach me at my personal email or on LinkedIn.

I’m a well-rounded software engineer, familiar with various software development practices, tools, and concepts. I’ve had success getting on board with large, legacy code bases as well as starting from a clean slate. I enjoy refactoring and improving code, even if I didn’t write it, and try to prioritize doing things “the right way” while also remaining practical and getting things done. Computers and tech are both my profession and my hobby, so I tend to stay pretty up-to-date even in areas I’m not working on specifically. I strive to be kind and compassionate in all areas of my life and treat every person with respect and dignity.

I have a few particular interests and specialties that make me stand out:

- Programming languages: I love learning new languages, and I especially like learning how they work. Most of my professional projects have involved parsing, implementing, analyzing, and troubleshooting formal languages, and I love that kind of work in particular.

- Domain-specific languages: I wrote about the benefits of DSLs a few years ago, the tl;dr is that if you’re doing a lot of technical writing in a very constrained way with strict rules about the “right” way to phrase things, or are using a specialty notation, you might get a lot of benefit out of defining a language and model for the work you are doing rather than doing it in a Word document. This is also closely related to the model-driven development approach that is becoming more popular. A custom-built tool doesn’t have to be hard to make, can have a shared understanding of the relevant concepts with its users, can do error checking, and if you’re writing something that eventually becomes code, may even be able to generate the code for you, with greater consistency than an engineer doing it manually. Definitely reach out if that rang a bell for you.

- Data parsing, translation, and transformation: Extracting data from one format and converting it to another, whether it’s a one-off task or an ongoing service, is something I have done many times. It requires thorough consideration of possible inputs, testing for robustness and correctness, and a solid understanding of both the input and output formats. And if you’d like to have a round-trip conversion that preserves all data in both directions, that introduces still more considerations which I have experience dealing with.

- Formal methods and safety-critical systems: My research career was in these areas and they still hold a lot of interest for me. I have experience in model checking and test-case generation with SMT solvers, writing software requirements in sufficient detail for safety-critical work, and a general healthy skepticism for processes that don’t put in the work to get things right when lives are on the line.

- Education and teaching: I have done a lot of tutoring and teacher assistanceships, and I like to think I’m good at breaking down ideas and helping others to learn them. Concepts in software are often very abstract and can be hard to understand without a lot of background, so communicating ideas to laypeople in a way that is both understandable and not an overwhelming information dump can be a tricky balance.

But really, I’m confident in my ability to learn and get useful at just about anything in the software engineering realm, even if I haven’t worked on it professionally yet. It’s one of the few areas in life where I don’t feel particularly humble; I’m good at what I do and I like doing it.

Personal

Much of my web experience comes from personal projects rather than professional ones, strangely, it’s just kind of how my career has happened to go. In one particular corner of the internet, I’m known for my copious cataloging of a very silly Apple prediction game on a fantastic podcast, Connected. That database of statistics, nonsense, and passion is implemented in a very fun and deeply weird tool called TiddlyWiki, which pretends to be a weird little single-file wiki system but is actually a minimal but powerful self-contained web app platform that they have used to make a weird little single-file wiki system. If you know what you’re doing, you can do some pretty incredible things with it. I’ve also used TiddlyWiki to make a Super Bowl prediction game that I run for my friends every year, and I was even doing my task management in a private TiddlyWiki, complete with categories, start dates, due dates, and personal calendar integration. If I had known about it when I was into Battlestar Galactica (the board game) enough to write my own comprehensive and dynamic rulebook for all the various expansions that would’ve probably been a TiddlyWiki too.

In addition, I run my own personal media server and some web services on it for myself, running a web server the “old fashioned way” although I do turn to Docker sometimes when it’s warranted, and I’ve dabbled in some web scraping and data preservation for some of the things I care about.

Specific projects

Here are some projects that I have been deeply involved with to give a more concrete idea of my skills.

Kotlin is a very interesting language, which I hadn’t used until a few years ago. It’s primarily built on the Java Virtual Machine platform and is common especially in Android development. I was tasked with implementing a type-safe builder in Kotlin for a file conversion project. This is a particular style of DSL which allows creating a pseudo-language within Kotlin that compiles as Kotlin code but looks and acts as if the language has incredible first-class support for things that it really doesn’t. I wrote about this a few years ago and it’s still one of my favorite projects that I’ve worked on.

The data format in question is fairly straightforward XML, which of course the Java/Kotlin ecosystem supports thoroughly, but by implementing it in a DSL, I essentially created a document templating language for our company’s specific format, with type checking, autocomplete, and even some support for the semantics of the document, not just the structure. Using it looks something like this:

val artifacts; // Incoming data has been pre-parsed already

val document = rootNodes {

threatsCatalog {

// Mixing and matching between DSL and normal Kotlin forEach loops

artifacts.filter { it.type == THREAT_CLASS }.forEach { threatArtifact ->

catalog.add(ThreatClass()) { tc ->

tc.name = threatArtifact["name"]

tc.title = threatArtifact["title"]

// continue building the object, maybe dive into other artifacts, etc.

}

}

}

}

Doing it in a DSL and not just a generic XML library means that the Kotlin compiler is providing structure and error checking about the output format, and the IDE is able to provide in-line documentation and autocomplete, ensuring many errors are corrected before the code even runs. While working on this project, I had to consider not just getting the thing to work, but also the experience of using it. A DSL like this has a tendency to “bend” the language in ways that aren’t always intuitive, and there were a few cases where I discovered that while something did work, it was clunky, unintuitive, misleading, or hard for the IDE to present to the user clearly.

In addition to creating the DSL for this data converter, I also worked on enabling a “round trip” conversion in both directions between this native format and an Excel representation. This was originally a single direction, intended to help new customers bring their data to our threat and risk assessment tool, but I expanded it to also convert from native back to Excel. This required a lot of work to preserve important identifiers in a way that was both robust and didn’t get in the way for a human looking at the data in Excel.

Honeywell has developed a language called CLEAR for writing software requirements, as well a tool called Text2Test for analysis of requirements written in that language. CLEAR reads like a natural language specification, but is specified by a grammar and semantics which make it possible for software to parse and understand. Text2Test was built on top of HiLiTE, an internal tool at Honeywell used for requirements-based verification written in C#. It takes CLEAR requirements and translates them into the existing structures that HiLiTE uses, which enables analysis and automatic test generation.

For example, if one were writing software for a microwave, one requirement may say something like When COOK_TIME > 0, the magnetron shall be ACTIVE while another says When DOOR_STATUS is OPEN, the magnetron shall be INACTIVE. Both entirely reasonable on their own, but these actually contradict one another in the case where a person opens the door while the oven is active. Text2Test is capable of detecting this contradiction and raising a warning about it.

I was initially hired as an intern to work on this tool, and was hired full-time afterward. I worked on finding and fixing bugs in Text2Test, as well as adding new features. Typically, this included modifications to the grammar for parsing CLEAR and code to implement the semantics of the new grammar. I needed to quickly get up to speed on a large existing codebase, and work within that codebase to add new features as well as find and fix bugs that came up during development. I also worked on a text editor for CLEAR, implemented as an Eclipse plug-in built with Xtext.

In addition to this more direct coding work, I also was involved in the bigger picture of finishing the language specification of CLEAR, putting forward my thoughts on how best to make the language unambiguous and easy to use. While our team spent a lot of time thinking about requirements, ambiguity, and the intuitive versus technical meanings of words, our users wanted to get their requirements done and get to the other things as well, so we were always listening, learning, and considering their needs when trying to create a tool that was as useful as possible to them.

TPlex, program analysis project

I worked on automated test case generation for PLEXIL, a planning language created by NASA. Automatic test case generation using SMT solvers is a well-known technique for automatically creating test inputs that satisfy a given property, but PLEXIL plans are intended for use in an autonomous system. As such, PLEXIL plans often require long test cases to achieve code coverage, because the system needs to make sure that both itself and the environment are in an expected state before proceeding. Since SMT solvers require exponentially more time as the length of a test case increases, the straightforward approach is not sufficient.

I wrote a translator to convert PLEXIL plans into Lustre, which is a modeling language used by the model checker JKind. The tool had to read in plans, represent them in an abstract syntax tree, convert them into an intermediate representation, perform compiler optimizations like constant propagation, pruning built-in variables that were unused, dead code removal, and finally convert the itermediate representation into its target language.

With this tool, we could automatically generate tests for PLEXIL plans, but scalability quickly became a limiting factor. I worked on using incremental test case generation, working toward an overall goal one achievable segment at a time. With this technique, it is critical that each segment makes progress toward the goal. I hoped to show that knowledge of the plan and the semantics of the language could be used to guide the search for a particular test case.

27 Jul 2023

As an undergraduate, someone in my dorm building came to me asking for help for an introductory computer science class I had taken the year before. I had cruised through the class and learned a lot, so I was eager to help out. As I watched her work through the problems, however, I was at a complete loss. I wanted to help her learn, not just do the assignment for her or tell her what keys to type, but she just didn’t seem to get it. When something went wrong, she seemed to be making changes at random, hoping they’d fix it with no apparent understanding of what was wrong in the first place. The concepts I had explained moments before seemed to go in one ear and out the other. Eventually, I found an excuse to leave and ran off, because I could tell that if I didn’t bail out I’d just end up doing the whole assignment and she wouldn’t have learned a thing.

That moment stuck with me, and it came up again in graduate school when I took a course on teaching in higher education and we were asked to think back to moments where we had had teaching-related difficulties. I was embarrassed at my past inability to help her, and if I was going to be helping teach students as a part of my assistanceship, I couldn’t just leave students like that hanging like I did before.

It did bring up the question, though: are there people who just can’t pick up the skills? I know I’ll never be an Olympic gymnast, I’ve never had any flexibility whatsoever, but does it require a particular type of brain to code? Naturally, the question has been asked and debated many times, but spoiler alert: the real pro move in situations like this is to go further and question the entire premise. What does it even mean to program, and does it even make sense to divide people into “can code” and “cannot code”?

An Army of Prometheuses (Prometheses? Promethesi?)

In the olden days, computers were kept behind the walled garden of large corporations and academia, with only a few trusted acolytes, punch cards in hand, allowed onto the floor where they kept the computer. “The Mother of All Demos”, as it came to be known, presented a radically different and shockingly prescient vision of what computing could be all the way back in 1968: windows, a pointer controlled by a mouse, links, and even remotely editing a document together with someone while on a video call with them, but it was so ahead of its time that it took decades for the rest of the world to make these things a practical reality.

As computers got smaller and more accessible, more effort was put into bringing the fire down from the mountaintop, easing the learning curve, and making them more broadly useful. BASIC was created with the explicit goal of enabling any student to use a computer without having to struggle with terse, unintuitive commands. VisiCalc for the Apple II made the tedious effort of filling out a numerical spreadsheet happen instantaneously, with no chance of simple arithmetic errors, using a layout that accountants were already familiar with. The graphical user interface spent valuable memory and processor cycles to present users with a more understandable metaphor for computing than the opaque incantations of the command line. Apple pushed the effort further with HyperCard and its associated language HyperTalk, which was designed to do real, honest-to-goodness programming while also feeling like natural language:

function replaceStr pattern,newStr,inStr

repeat while pattern is in inStr

put offset(pattern,inStr) into pos

put newStr into character pos to (pos +the length of pattern)-1 of inStr

end repeat

return inStr

end replaceStr

Today, “low code” and “no code” platforms are among the latest efforts to, if not eliminate the programmer entirely and let a non-technical person build a tool for themselves, at least give the programmer tools to quickly whip something together without having to do a bunch of busy work first. The humble Excel spreadsheet continues to be, for better or for worse, pressed in to service where it may not be the best tool for the job solely because of how accessible it is. Every iPhone comes pre-loaded with a surprisingly powerful automation tool, Shortcuts, that allows users to assemble scripts out of drag-and-drop blocks and run them on demand or automatically in response to events. And the sudden and rapid rise of large language models like ChatGPT and GitHub Copilot, capable of creating… well, something that at least looks like the right code from just a few unstructured sentences, is one of the first things to cause programmers to seriously consider whether their career is about to be automated away entirely, an ironic twist of fate that, well, maybe we deserve if it ever comes to pass. (Of course, to get any AI to write a program for you, you’ll first have to clearly and unambiguously explain what it is you need, and as someone who has looked at a lot of software requirement documents… good luck.)

Oh, you like programming? Name every algorithm

The era of computing has reached a point where it’s not at all unusual for even the least tech-savvy person to carry around a few computers as they go about their normal life. Access to the global network of computers is often considered a human right. Short of strapping one to everyone’s face, it’s hard to imagine how computing could become more ubiquitous or accessible, and it certainly has never been more important, and yet as of 2023, there are still some people in the world who aren’t programmers [citation needed]. In fact, one must assume that there are more people who struggle to get their email to work right or print a document than know how to automate something tedious in their lives. So did we fail despite all that effort? Should the joke two headings ago have been about Sisyphus instead of Prometheus?

When considering accessibility in the typical sense, for people with things like vision or hearing impairments, it’s useful to reframe issues from individual to systemic: it’s not that “this person can’t do this thing and we need to help them fix their problem,” the problem is that that we have collectively erected a barrier and the right thing to do is remove it if possible. This encourages bigger, more complete thinking, and is likely to solve problems for a broader group of people. When it comes to software, a lot of the problems people have with it are not their fault at all, they’re due to the fact that, in many ways, our entire field is bad at what we do when compared to, say, the “real” engineers that can mostly reliably build and maintain a bridge that does its job without requiring a reboot every few months to get it working again. But even in an idealized world of bug-free software, it’s hard to imagine all of our friends and family being enabled to write a program to solve a problem with the powerful computer they carry around all day using the tools we currently provide them.

That may be overstating the actual problem, though. Programming is a useful and lucrative skill, but it’s not necessary to get lots of other useful things done using a computer. And it’s also not a binary, no pun intended. There are degrees that people can choose to rise or fall to as they wish and as the situation warrants. Early on, getting a computer to do anything required knowing the exact series of electrical impulses to send over wires to get the behavior you wanted. Then one merely needed to know the names and functions of programs available on a command line and how to chain them together. Later, just knowing what files and folders were, and how to open them in the right program to edit them would get you most of the way there. Today, kids are making it all the way to college without needing to learn what a file is because modern computing platforms have abstracted the idea away in favor of something simpler and easier to use.

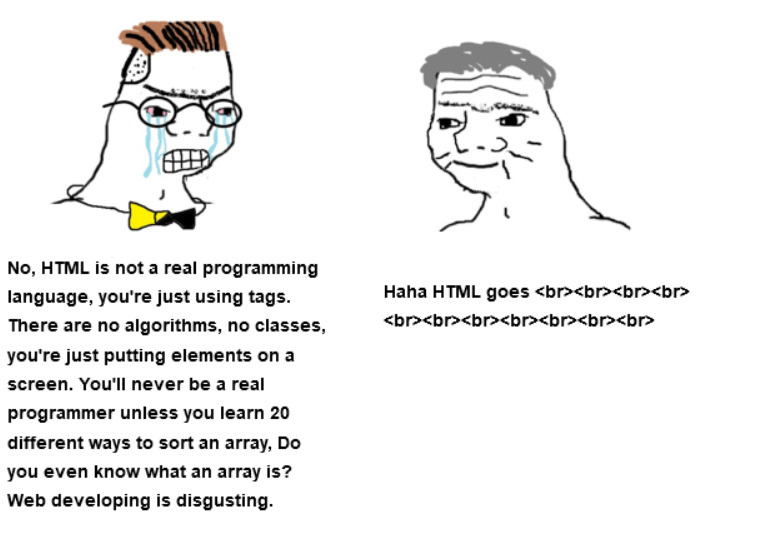

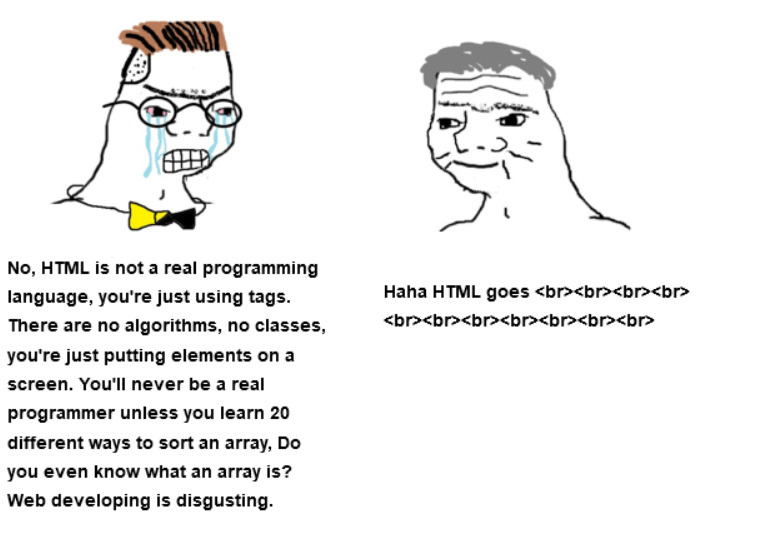

Along the way, regular people have found ways to make computers work for them as they became accessible to their skill level. It wasn’t always pretty, there has been plenty of magical thinking and cargo culting without the solid grasp of the fundamentals that a formal education might establish, but the tools are often there and people make do. In the wild frontier of the early web, amateur webmasters were copy-pasting HTML to cobble together their own site just the way they wanted it, and though HTML isn’t a programming language… isn’t it kind of a programming language? Issuing structured instructions to a computer to get it to do what you want? The open nature of the source of a webpage and the straightforward markup lowered the accessibility bar to the point that lots of people were able to publish whatever they wanted to the world, all without ever inverting a binary tree on a whiteboard.

Maybe our job isn’t to make everyone a programmer, but to meet them where they are and help them do what they want to do. After all, I’d roll my eyes at a blog post by a mechanic bemoaning how people can’t change their brake pads anymore — I’m sure I could figure it out, eventually, but I have no interest in learning that skill to the point where I could put my safety on the line, I’d rather have an expert do it, and that’s fine too. As long as it gets done, I will have the accessibility that I ask my car to provide to me.

Domain-specific languages: a meeting of the minds

It’s a great thing to create a cool, easy-to-use tool, give it to the world, and say “Go forth and create things, my common people!” but sometimes those of us who are building the software have the opportunity to create something more specialized. While not every problem can be solved by throwing a smart programmer at it, sometimes the people who know computer stuff and the people who know other stuff can work together to do some cool stuff with the stuff they all know.

Traditionally, this has been accomplished by a defined software development process, which usually looks something like “the software people grill the experts on what is needed, then go off and write some code, the experts try it and give feedback, repeat until it’s good.” One problem that comes up is that it’s hard to know what is easy and what is hard in programming, resulting in frustration when someone says “just make a button that does X!” Another is that, as mentioned before, software requirements are hard. The moment we’re having in machine learning right now is the first time we’ve ever been able to tell a computer “uh, here’s some examples of what we want, figure it out” and get anything decent out, but we’re still in the very early days of that. For everything else, every single vague idea must get clarified into something specific, and if it doesn’t get done intentionally, it’ll get done unintentionally as the programmer makes a guess, makes an assumption, or uses someone else’s code and gets whatever that other person decided.

And in that general process, note that the expert is in the loop, but only periodically. The domain expert is a critical part of building the software, since they’re the ones who know what is right and what is wrong, but their expertise isn’t in writing code, so we filter their knowledge through others and hope that it makes it through into the code all in one piece. Seems inefficient and error-prone. But they can’t write the code themselves, so if we want to fix this, we’re back to the same problem again: can the domain expert be taught to code?

After all this setup, hopefully the solution seems obvious: if the code base currently requires the ability to code to contribute, instead of changing the person, could we remove or lower that barrier? Maybe the domain expert doesn’t have to become a general software engineer for us to get them more tightly integrated if we put a bit of effort in to make the software development process itself accessible and useful to them. What does that look like?

- They can do what they do best: provide important knowledge about the thing they’re good at

- Once they get set up and learn the ropes, they can contribute without constantly needing help from others

- They can do their part of the process with a similar cadence as the programmers: write something, run, get feedback about problems, fix problems, repeat.

The hard parts of programming are that it requires detailed knowledge about a lot of abstract ideas and nested layers of systems, and you have to predict how everything will interact as you write very specific instructions that will be followed exactly as written and not intended. Programmers quickly get good at questioning all of their assumptions because they’re reminded, repeatedly, in scary red letters, that what they thought was true is actually wrong, to the point where if something works on the first try they start getting very suspicious. That’s exhausting, and it makes perfect sense that most people don’t want to put themselves through that amount of constant frustration.

Let’s spare the domain expert as much of that as we can. They don’t need to know the whole system, or learn the intricacies of recursion or efficient loops or the software platform’s long list of features. The ideal would be writing code in a language just for them, focused on their domain and the tasks they need to accomplish, and all the other stuff could be hidden away or delegated to someone else who can work on the details alongside the expert.

This is exactly where a domain-specific language can be an incredibly useful tool. DSLs are not general programming languages, so one might not be able to write a loop or function or call out to libraries, instead they are focused on a particular task and the details of what happens to the content written in the language are all behind the scenes in the implementation. HTML is a domain-specific language — it can’t be used to write a program except by embedding JavaScript in it, but it does support features specific to the domain of creating a hyperlinked multimedia document, and all the details of rendering that document are implemented in web browsers. Regular expressions are another example, a very compact miniature language embedded within many tools and general programming languages, which are restricted to the domain of searching and manipulating text non-recursively.

More modern programming languages have begun including features that enable the creation of domain-specific languages inside of the language as a whole. Rather than having to write an entire toolchain for parsing the DSL, translating it into some other form of code, and integrating it with the larger system, a DSL in this style is valid code in the language, it’s just structured to look a particular way and hide the implementation details somewhere in a library where users of the language don’t have to worry about it. My previous blog post showed an example of this, an HTML DSL that looks like a purpose-built language but is actually “just” Kotlin code.

var myHtml =

html {

head {

title { +"My super cool blog post" }

}

body {

h1 { +"My super cool blog post" }

p { +"If you're anything like me, you think a lot about work, play, and dullness." }

for (i in 0..100) {

p { +"Jack's dull boy levels have reached $i." }

}

}

}

}

There are a few useful advantages to such an approach as compared to creating an entire new language from scratch:

- There’s already a compiler, toolchain, and access to create the implementation of the DSL

- There’s already a tool for writing in the DSL that includes nice things like autocomplete, error highlighting, etc.

- The DSL is interoperable with the host language because it is the host language

- If more general programming tools are sometimes required, they’re accessible (see above, where a Kotlin

for loop is used within the DSL)

- The host language’s type system is available to help create structure and flag errors

The approach does come with some caveats, however:

- It takes time and effort to make a good DSL, and it’ll need to be good to be easy to use, so the cost and benefits need to be weighed

- The host language’s rules still have to be followed; if it’s a good fit this shouldn’t be an issue but if the host language isn’t flexible enough, the DSL might be weird or clunky

- It’s still programming, debugging is still hard, and if you’re bending the language in weird ways the error messages might be hard to understand without even more language design effort

When a DSL is a good fit, someone on the software engineering team can implement one using the general language that the tool is written in, with the collaboration of the domain expert to know what concepts and ideas are necessary to express. Once the language is going, the expert can start capturing ideas and writing real code, while the rest of the team uses the results of that language to implement the rest of the project. It can become a more collaborative and interactive effort, with the domain expert closer to the code and able to get a first-hand look at how the programmers are implementing their ideas, and the programmers explicitly creating an interface between “their stuff” and “the expert’s stuff” which can clarify concepts and force the two sides to negotiate what is supposed to be happening instead of guessing or assuming. The domain expert may even be able to participate in the testing and debugging process.

As an example, let’s imagine an app for learning chess openings and history. Our chess grand master is in charge of writing these tutorials and articles, including interactive chess boards for the user to see for themselves and maybe even try some variations on the ideas. She’s already fluent in algebraic notation for chess, so reading and writing things like this doesn’t phase her one bit:

1.e4 c5 2.c3 d5 3.exd5 Qxd5 4.d4 Nf6 5.Nf3 Bg4 6.Be2 e6 7.h3 Bh5 8.0-0 Nc6 9.Be3 cxd4 10.cxd4 Bb4 11.a3 Ba5 12.Nc3 Qd6 13.Nb5 Qe7 14.Ne5 Bxe2 15.Qxe2 0-0 16.Rac1 Rac8 17.Bg5 Bb6 18.Bxf6 gxf6 19.Nc4 Rfd8 20.Nxb6 axb6 21.Rfd1 f5 22.Qe3 Qf6 23.d5 Rxd5 24.Rxd5 exd5 25.b3 Kh8 26.Qxb6 Rg8 27.Qc5 d4 28.Nd6 f4 29.Nxb7 Ne5 30.Qd5 f3 31.g3 Nd3 32.Rc7 Re8 33.Nd6 Re1+ 34.Kh2 Nxf2 35.Nxf7+ Kg7 36.Ng5+ Kh6 37.Rxh7+ 1–0 (source)

We want this app to be fancier than a blog post, with interactive features and integration into code for playing with the scenarios being described, so we want data like this to be usable in code, not just as text. We could try to write a parser for this notation, or have a programmer translate it by hand into code that looks something like

val kasparovDeepBlueGame1 = ChessGame()

kasparovDeepBlueGame1.add(Move(Square.e4))

kasparovDeepBlueGame1.add(Move(Square.c5))

kasparovDeepBlueGame1.addCommentary("For playing against Kasparov, the IBM team chose not to play the typical...")

kasparovDeepBlueGame1.add(Move(Square.c3))

… but this isn’t ideal. A parser would do the trick, but that’s a lot of work and then it still has to be integrated into the app’s code. When a programmer does the translating, writing is being done twice, with a tedious translation process by someone who isn’t the expert into a verbose, repetitive notation. The expert will have to do all the writing, wait for a new build, then try it herself as she’s the only one likely to notice chess errors. She herself is clearly capable of writing in a formal notation, though, so a DSL that comes closer to what she needs and is already familiar with could enable her to do the writing and programming herself.

val kasparovDeepBlueGame1 = game {

// 1.

e4(); c5(); comment("For playing against Kasparov, the IBM team chose not to play the typical...");

// 2.

c3(); d5();

// 3.

d5(Rank.E, Note.X); d5(Piece.Q, Note.X);

...

}

With some structure and guidance, the grand master could write and do some debugging for an entire tutorial on her own without having to go through an intermediary, while behind the scenes the software developers are doing some extra lifting to present this simpler interface to her:

@ChessNotation

class ChessGame {

fun comment(text: String) : Unit = { ... }

fun a1(piece: Piece? = null, rank: Rank? = null, vararg notes: Note) : Unit = { ... }

fun a1(rank: Rank? = null, vararg notes: Note) : Unit = { ... }

fun a1(piece: Piece? = null, vararg notes: Note) : Unit = { ... }

fun a2(piece: Piece? = null, rank: Rank? = null, vararg notes: Note) : Unit = { ... }

fun a2(rank: Rank? = null, vararg notes: Note) : Unit = { ... }

// TODO: we either need a better way to do this, or just have the intern do the rest, ugh

}

fun game(init: ChessGame.() -> Unit) : ChessGame {

val theGame = ChessGame()

theGame.init()

return theGame

}

It could also include some basic sanity checks to flag errors right away as she’s testing, and it can use the language’s type system to ensure that some errors get flagged by the compiler right in her development environment. She’ll also have a much more direct idea of what the software is and is not capable of, and is better equipped to ask for new features when she has a brilliant idea while writing. She might even be able to write out an example of how she’d like it to be notated in the DSL, giving the language implementers a clear and concrete task instead of a vague description.

The answer: Yes, if we lend a hand

It takes time, design effort, and thoughtful work to create a DSL that works well and is easy to use. That effort has to be balanced with the cost of taking time to make such a thing that could otherwise be spent banging it out in a less nice way. But in many scenarios, a DSL can make for a better process, and it can enable people to program that never saw themselves as master hackers. It’s not accessibility in the way we typically think of it, but by meeting people where they are and helping them to get more directly involved, we can increase the diversity of skills in the team and hopefully produce a better product faster as a result.

06 Jul 2023

Kotlin is a popular language for JVM-based development, and it’s easy to see why: decades of work have gone into the Java ecosystem and libraries and Kotlin can interoperate with all of them, but as a younger language, Kotlin is able to avoid some of the clunkiness that Java is encumbered with, while adopting programming language concepts that have (re)gained popularity in the 21st century, like first-class functions, immutable types, and more careful handling of null.

One good example of Kotlin’s flexibility is its support for creating limited domain-specific languages, all just by using features that Kotlin already has. Kotlin’s excellent documentation has a few chapters on this with an HTML example, but as I’ve worked on a similar structure for writing out an XML-based document format, some useful extensions to that example have emerged.

Creating a simple builder DSL in Kotlin

This section will be a quick summary covering the same material as the above documentation, so if you’re already familiar with type-safe object builders, feel free to skip to the next section to see the new ideas.

Kotlin builder DSLs use a few Kotlin language features together to create notation that is so minimal that it almost looks like a completely custom langauge:

var myHtml =

html {

head {

title { +"My super cool blog post" }

}

body {

h1 { +"My super cool blog post" }

p { +"If you're anything like me, you think a lot about work, play, and dullness." }

for (i in 0..100) {

p { +"Jack's dull boy levels have reached $i." }

}

}

}

}

The for loop looks like normal Kotlin, but surely Kotlin doesn’t have first-class language support for HTML tag blocks like this. What’s going on here?

The most important trick is that in Kotlin, lambda expressions that come last in the list of a function’s arguments can be written outside the function call. Instead of writing

list.forEach( { foo -> foo.bar() } )

you can move the lambda code block outside of the function, and if there are no other arguments you can also omit the parentheses, and the result looks very similar to built-in language constructs like for and while:

list.forEach {

foo -> foo.bar()

}

The next trick is function types with receiver, which allow functions to be written as if they belong to a type without actually modifying that type, complete with support for referring to the object as this. This allows programmers to add functionality to objects without requiring the ability to modify the class directly:

// Anywhere this function is visible, it will be available for Strings as if it were built in

fun String.clapBack(): String {

return this.split(" ").joinToString("👏").uppercase()

}

println("Hot dogs are not sandwiches and it's silly to argue about it".clapBack())

// HOT👏DOGS👏ARE👏NOT👏SANDWICHES👏AND👏IT'S👏SILLY👏TO👏ARGUE👏ABOUT👏IT

(Technically this is an extension function, which is not exactly the same thing as a lambda with a receiver type, but they are basically the same idea.)

Finally, the + in front of the strings in the HTML DSL is an operator override of unaryPlus, in this case being used to define a shorthand for adding the String literal to the object being constructed. A verbose but more intuitive way to do this would be to just have a normal function call or property assignment, like title { this.content = "My super cool blog post" }.

Now we can start to understand what’s going on in the example above. Although the html, head, title, etc. blocks look a bit like static data, they are actually functions, with lambda expressions as their arguments. Each one is responsible for creating, building, and structuring an object, and since they are all functions, the type system of Kotlin can ensure that everything is structured correctly. As the Kotlin documentation points out, each of these functions are doing basically the same thing, just with different types of object, so a single generic version can be reused for all of them.

// Non-generic versions of the builder functions

fun head(init: Head.() -> Unit): Head {

val head = Head()

head.init()

children.add(head)

return head

}

fun body(init: Body.() -> Unit): Body {

val body = Body()

body.init()

children.add(body)

return body

}

// But doing it this way is less redundant

protected fun <T : Element> initTag(tag: T, init: T.() -> Unit): T {

tag.init()

children.add(tag)

return tag

}

fun head(init: Head.() -> Unit) = initTag(Head(), init)

fun body(init: Body.() -> Unit) = initTag(Body(), init)

Each builder function handles all the work of creating the object, running the user-supplied lambda expression (inside of which the user can treat this as the object being created), putting the new object where it belongs, and returning the final result. When actually building the object, the only thing that needs to be specified is how each object is to be initialized, the rest is hidden away inside the implementation of the DSL.

Keeping builder functions in one place

This pattern works to create the useful pseudo-language above, where a document can be laid out in a structured way but still get the benefit of type checking, as well as the ability to mix in Kotlin code like loops and custom functions. It’s easy to use, easy to read, and easy to understand. But inside the library, the small code example in the documentation above has an organization issue. One abstract class looks like this:

abstract class BodyTag(name: String) : TagWithText(name) {

fun b(init: B.() -> Unit) = initTag(B(), init)

fun p(init: P.() -> Unit) = initTag(P(), init)

fun h1(init: H1.() -> Unit) = initTag(H1(), init)

fun a(href: String, init: A.() -> Unit) {

val a = initTag(A(), init)

a.href = href

}

}

Naturally, all the body tag types extend this one, and that works well to put common functionality in one place. But this is actually a little too permissive — it allows constructing documents that probably should not work:

var wat =

html {

body {

p {

h1 { +"Don't headings usually go outside of paragraphs?" }

}

}

}

With all the builder functions in one place, they are also usable everywhere, even when they shouldn’t be. It would be nice if the DSL helped enforce more structure. We could break up the BodyTag class into “block” and “inline” variants in this particular case, but if our needs get more complex, issues will start to arise.

- Having these builder functions sprinkled in anywhere they need to be accessible, even if they’re one-liners like most of these, is unnecessary code duplication.

- The anchor tag

a href builder has a useful customization where the address can be specified immediately, but if we want that anywhere an a tag is allowed, each version will need to have that same addition, and updating or changing it later will require keeping them all in sync… now that’s really starting to smell. It’s time to step back and rethink this a bit.

Ordinarily, how an object is constructed is a job for the class, not what’s using the object. Normal constructors, of course, go in the class definition, and even if an object’s creation is complex enough to use something like a factory pattern, it’s going to be closely tied to the object in some way. Is there a way we can keep these builder functions in one place, but make them available everywhere they’re allowed?

Well, yes, of course. This would be a very anticlimactic post otherwise.

It isn’t possible to import individual functions, but it is possible to put functions with default implementations into an interface and extend it in multiple places. The interface can even (usually) be nested inside the class itself to keep things very neat and tidy.

/**

* This interface gives the various Builders access to functions they need.

* The `Tag` class was modified slightly to add this interface, it already has the implementation.

*/

interface BuilderBase {

fun <T : Element> initTag(tag: T, init: T.() -> Unit): T

}

// If some builders tend to be bundled together, another interface can collect them

interface ContainsInlineTags : BBuilder, ABuilder

interface ContainsBlockTags : P.Builder, H1.Builder

// These interfaces will pull in the builder functions, and since they have default implementations

// that any Tag is already able to use, all that's needed is to extend them.

class Body : TagWithText("body"), ContainsBlockTags, ContainsInlineTags

// A Tag with its builder function interface embedded in the class.

class P : TagWithText("p"), ContainsInlineTags {

interface Builder : BuilderBase {

fun p(init: P.() -> Unit) = initTag(P(), init)

}

}

class H1 : TagWithText("h1"), ContainsInlineTags {

interface Builder : BuilderBase {

fun h1(init: H1.() -> Unit) = initTag(H1(), init)

}

}

// Unfortunately, embedding the interface gets trickier when tags are more recursive. Doing it as

// above results in an inheritance cycle. If you've got an approach that gets around this, I'd love

// to hear about it.

interface BBuilder : BuilderBase {

fun b(init: B.() -> Unit) = initTag(B(), init)

}

class B : TagWithText("b"), ContainsInlineTags

interface ABuilder : BuilderBase {

fun a(href: String, init: A.() -> Unit) {

val a = initTag(A(), init)

a.href = href

}

}

class A : TagWithText("a"), ContainsInlineTags {

var href: String

get() = attributes["href"]!!

set(value) {

attributes["href"] = value

}

}

By keeping builder functions in one place, users of the DSL will have a more consistent experience, it becomes very easy to put builders only where they make sense, and developers will be able to make changes more easily. In addition, this approach is optional for every class involved, and if a different style of builder is warranted in one place, it can be implemented and the default version from the class can be ignored.